This is a note from < CUDA C++ Programming Guide > published by nvidia. “Changes from Version 12.2”, so its’ reasonable that some features can’t be applied on old device.

Note that:

- it’s 1/1/2024. Most common GPUs is of core architecture

Ampere. Some knowledge can be out-of-date and I will skip them. - I will skip some knowledge that are common and basic.

1. introduction

There are 3 types of versio, version of cuda toolkit, cuda driver and GPU driver. You can treat cuda toolkit as cuda runtime.

Starting with CUDA 11.0, the toolkit components are individually versioned, and the toolkit itself is versioned as shown in the table below.

Each release of the CUDA Toolkit requires a minimum version of the CUDA driver. The CUDA driver is backward compatible, meaning that applications compiled against a particular version of the CUDA will continue to work on subsequent (later) driver releases. Version of cuda driver should be higher than that of cuda toolkit.

You can find details of compatibility cuda-toolkit and cuda-compatibility.

2. Programming Model

2.1 Kernels

2.2 Thread Hierarchy

On current GPUs, a thread block may contain up to 1024 threads. A thread block size of 16x16 (256 threads), although arbitrary in this case, is a common choice.

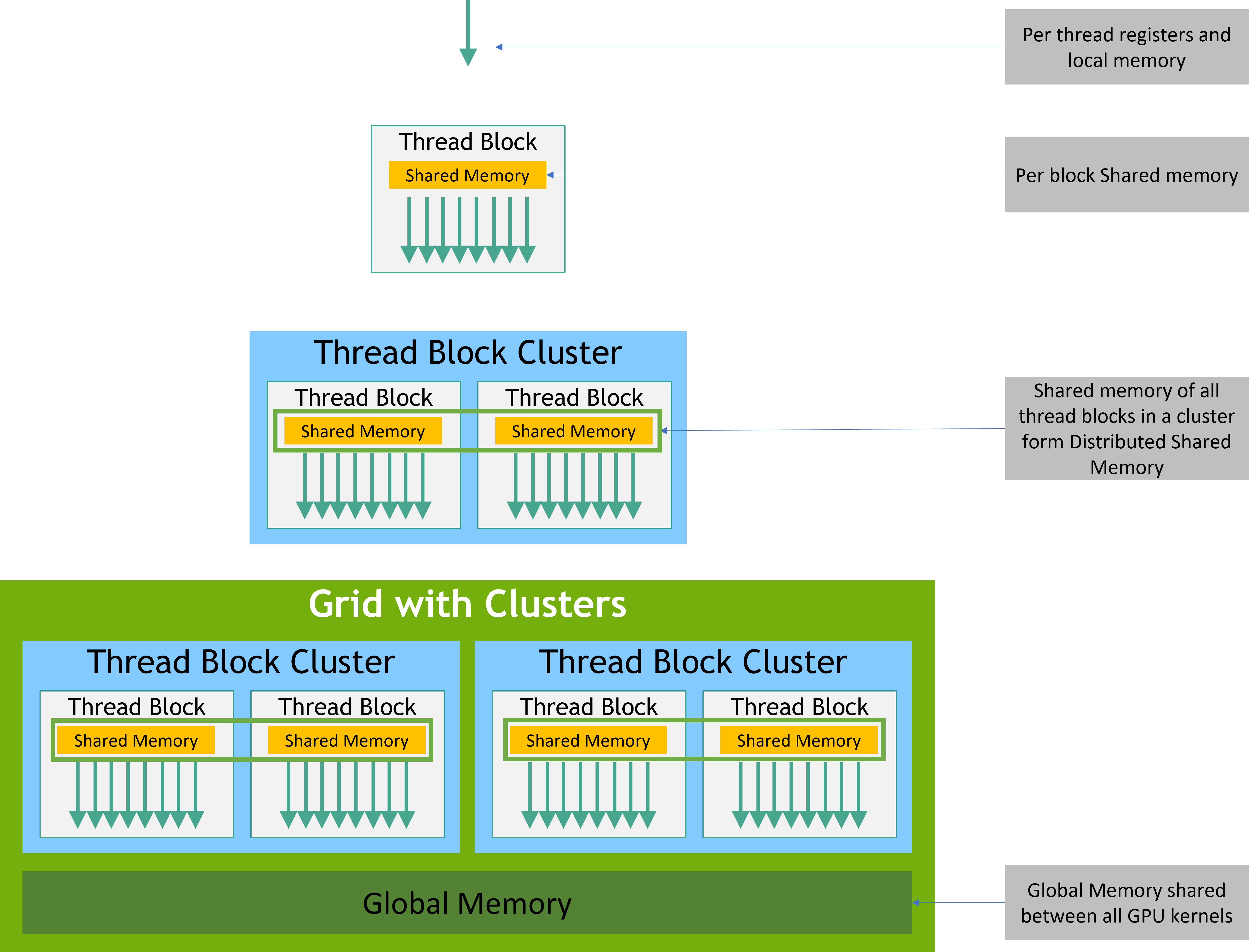

2.2.1. Thread Block Clusters

The number of thread blocks in a cluster can be user-defined, and a maximum of 8 thread blocks in a cluster is supported as a portable cluster size in CUDA. Note that on GPU hardware or MIG configurations which are too small to support 8 multiprocessors the maximum cluster size will be reduced accordingly. Identification of these smaller configurations, as well as of larger configurations supporting a thread block cluster size beyond 8, is architecture-specific and can be queried using the cudaOccupancyMaxPotentialClusterSize API.

The rank of a block in a cluster can be found using the Cluster Group API.

A thread block cluster can be enabled in a kernel either using a compiler time kernel attribute using __cluster_dims__(X,Y,Z) or using the CUDA kernel launch API cudaLaunchKernelEx.

Perform hardware-supported synchronization using the Cluster Group API cluster.sync().

The rank of a thread or block in the cluster group can be queried using dim_threads() and dim_blocks() API respectively.

Thread blocks that belong to a cluster have access to the Distributed Shared Memory. ???

2.3 Memory Hierarchy

2.4 Heterogeneous Programming

2.5. Asynchronous SIMT Programming Model

These synchronization objects can be used at different thread scopes. A scope defines the set of threads that may use the synchronization object to synchronize with the asynchronous operation. There are four slopes:

cuda::thread_scope::thread_scope_threadcuda::thread_scope::thread_scope_blockcuda::thread_scope::thread_scope_devicecuda::thread_scope::thread_scope_system

These thread scopes are implemented as extensions to standard C++ in the CUDA Standard C++ library.

2.6. Compute Capability

The compute capability of a device is represented by a version number, also sometimes called its “SM version”. The compute capability comprises a major revision number X and a minor revision number Y and is denoted by X.Y. Devices with the same major revision number are of the same core architecture.

| major revision | architecture |

|---|---|

| 9 | Hopper |

| 8 | Ampere |

| 7.5 | Turing |

| 7 | Volta |

| 6 | Pascal |

| 5 | Maxwell |

| 3 | Kepler |

The compute capability version of a particular GPU should not be confused with the CUDA version (for example, CUDA 7.5, CUDA 8, CUDA 9),which is the version of the CUDA software platform.

3. Programming Interface

3.1 Compilation with NVCC

nvcc is a compiler driver that simplifies the process of compiling C++ or PTX code.

Offline Compilation

nvcc:

- compiling the device code into an assembly form (PTX code) and/or binary form (cubin object)

- and modifying the host code by replacing the

<<<...>>>syntax introduced in Kernels by the necessary CUDA runtime function calls to load and launch each compiled kernel from the PTX code and/or cubin object.

Applications:

- Either link to the compiled host code (this is the most common case),

- Or ignore the modified host code (if any) and use the CUDA driver API to load and execute the PTX code or cubin object.

Just-in-Time Compilation

It is the only way for applications to run on devices that did not exist at the time the application was compiled.

When the device driver just-in-time compiles some PTX code for some application, it automatically caches a copy of the generated binary code in order to avoid repeating the compilation in subsequent invocations of the application.

NVRTC can be used to compile CUDA C++ device code to PTX at runtime. NVRTC is a runtime compilation library for CUDA C++.

Binary Compatibility

Binary code is architecture-specific. Compile with -code=sm_80 produces binary code for devices of compute capability 8.0. A cubin object generated for compute capability X.y will only execute on devices of compute capability X.z where z≥y.

Binary compatibility is supported only for the desktop. It is not supported for Tegra. Also, the binary compatibility between desktop and Tegra is not supported.

PTX Compatibility

Some PTX instructions are only supported on devices of higher compute capabilities. Note that a binary compiled from an earlier PTX version may not make use of some hardware features.

Application Compatibility

In particular, to be able to execute code on future architectures with higher compute capability (for which no binary code can be generated yet), an application must load PTX code that will be just-in-time compiled for these devices.

Host code is generated to automatically select at runtime the most appropriate code to load and execute, which, in the above example, will be:

- 5.0 binary code for devices with compute capability 5.0 and 5.2,

- 6.0 binary code for devices with compute capability 6.0 and 6.1,

- 7.0 binary code for devices with compute capability 7.0 and 7.5,

- PTX code which is compiled to binary code at runtime for devices with compute capability 8.0 and 8.6.

The __CUDA_ARCH__ macro can be used to differentiate various code paths based on compute capability. It is only defined for device code. When compiling with -arch=compute_80 for example, __CUDA_ARCH__ is equal to 800.

C++ Compatibility

The front end of the compiler processes CUDA source files according to C++ syntax rules. Full C++ is supported for the host code. However, only a subset of C++ is fully supported for the device code.

3.2 CUDA Runtime

The runtime is implemented in the cudart library. It is only safe to pass the address of CUDA runtime symbols between components that link to the same instance of the CUDA runtime. All its entry points are prefixed with cuda.

3.2.1 Initialization

Absent cudaInitDevice() and cudaSetDevice(), the runtime will implicitly use device 0 and self-initialize as needed to process other runtime API requests.

Before 12.0, cudaSetDevice() would not initialize the runtime and applications would often use the no-op runtime call cudaFree(0) to isolate the runtime initialization from other api activity (both for the sake of timing and error handling).

The runtime creates a CUDA context for each device in the system, which is shared among all the host threads of the application. When a host thread calls cudaDeviceReset(), this destroys the primary context of the device the host thread currently operates on.

The CUDA interfaces use global state that is initialized during host program initiation and destroyed during host program termination. Using any of these interfaces (implicitly or explicitly) during program initiation or termination after main will result in undefined behavior.

As of CUDA 12.0,

cudaSetDevice()will now explicitly initialize the runtime after changing the current device for the host thread. Previous versions of CUDA delayed runtime initialization on the new device until the first runtime call was made aftercudaSetDevice(). This change means that it is now very important to check the return value ofcudaSetDevice()for initialization errors.

3.2.2 Device Memory

Device memory can be allocated either as linear memory or as CUDA arrays.

Linear memory is typically allocated using cudaMalloc() and freed using cudaFree() and data transfer between host memory and device memory are typically done using cudaMemcpy().

Linear memory can also be allocated through cudaMallocPitch() and cudaMalloc3D(). These functions are recommended for allocations of 2D or 3D arrays as it makes sure that the allocation is appropriately padded to meet the alignment requirements described in Device Memory Accesses, therefore ensuring best performance when accessing the row addresses or performing copies between 2D arrays and other regions of device memory (using the cudaMemcpy2D() and cudaMemcpy3D() functions).

If your application cannot request the allocation parameters for some reason, we recommend using cudaMallocManaged() for platforms that support it.

cudaGetSymbolAddress() is used to retrieve the address pointing to the memory allocated for a variable declared in global memory space. The size of the allocated memory is obtained through cudaGetSymbolSize().

3.2.3 Device Memory L2 Access Management(skip)

Starting with CUDA 11.0, devices of compute capability 8.0 and above have the capability to influence persistence of data in the L2 cache, potentially providing higher bandwidth and lower latency accesses to global memory.

SKIP IT IS TOO HARD

L2 cache

3.2.4 Shared Memory

The code example is an implementation of matrix multiplication that does take advantage of shared memory.

3.2.5 Distributed Shared Memory

Thread block clusters introduced in compute capability 9.0 provide the ability for threads in a thread block cluster to access shared memory of all the participating thread blocks in a cluster. This partitioned shared memory is called Distributed Shared Memory, and the corresponding address space is called Distributed shared memory address space.

The size of distributed shared memory is just the number of thread blocks per cluster multiplied by the size of shared memory per thread block.

3.2.6 Page-Locked Host Memory

The runtime provides functions to allow the use of page-locked:

cudaHostAlloc()andcudaFreeHost()allocate and free page-locked host memory;cudaHostRegister()page-locks a range of memory allocated bymalloc()

Using page-locked host memory has several benefits:

- Copies between page-locked host memory and device memory can be performed concurrently with kernel execution for some devices.

- On some devices, page-locked host memory can be mapped into the address space of the device, eliminating the need to copy it to or from device memory.

- On systems with a front-side bus(a communication interface that transfers data back and forth between the CPU and the other components.), bandwidth between host memory and device memory is higher if host memory is allocated as page-locked and even higher if in addition it is allocated as write-combining.

Page-locked host memory is not cached on non I/O coherent Tegra devices. Also, cudaHostRegister() is not supported on non I/O coherent Tegra devices.

Write-Combining Memory

To make these advantages available to all devices, the block needs to be allocated by passing the flag cudaHostAllocPortable to cudaHostAlloc() or page-locked by passing the flag cudaHostRegisterPortable to cudaHostRegister().

Write-combining memory is not snooped during transfers across the PCI Express bus, which can improve transfer performance by up to 40%.

Reading from write-combining memory from the host is prohibitively slow, so write-combining memory should in general be used for memory that the host only writes to.

Reading from write-combining memory from the host is prohibitively slow, so write-combining memory should in general be used for memory that the host only writes to. Using CPU atomic instructions on WC memory should be avoided because not all CPU implementations guarantee that functionality.

Mapped Memory

Accessing host memory directly from within a kernel does not provide the same bandwidth as device memory, but does have some advantages:

- There is no need to allocate a block in device memory and copy data between this block and the block in host memory; data transfers are implicitly performed as needed by the kernel;

- There is no need to use streams (see Concurrent Data Transfers) to overlap data transfers with kernel execution; the kernel-originated data transfers automatically overlap with kernel execution.

Since mapped page-locked memory is shared between host and device however, the application must synchronize memory accesses using streams or events (see Asynchronous Concurrent Execution) to avoid any potential read-after-write, write-after-read, or write-after-write hazards.

Note that atomic functions (see Atomic Functions) operating on mapped page-locked memory are not atomic from the point of view of the host or other devices.

Note that CUDA runtime requires that 1-byte, 2-byte, 4-byte, and 8-byte naturally aligned loads and stores to host memory initiated from the device are preserved as single accesses from the point of view of the host and other devices.

3.2.7. Memory Synchronization Domains???

Beginning with Hopper architecture GPUs and CUDA 12.0, the memory synchronization domains feature provides a way to alleviate such interference. In exchange for explicit assistance from code, the GPU can reduce the net cast by a fence operation. Each kernel launch is given a domain ID. Writes and fences are tagged with the ID, and a fence will only order writes matching the fence’s domain.

When using domains, code must abide by the rule that ordering or synchronization between distinct domains on the same GPU requires system-scope fencing.

This is necessary for cumulativity as one kernel’s writes will not be encompassed by a fence issued from a kernel in another domain. In essence, cumulativity is satisfied by ensuring that cross-domain traffic is flushed to the system scope ahead of time.

Note that this modifies the definition of thread_scope_device. However, because kernels will default to domain 0 as described below, backward compatibility is maintained.Domains are accessible via the new launch attributes cudaLaunchAttributeMemSyncDomain and cudaLaunchAttributeMemSyncDomainMap. The former selects between logical domains cudaLaunchMemSyncDomainDefault and cudaLaunchMemSyncDomainRemote, and the latter provides a mapping from logical to physical domains.

The domain count can be queried via device attribute cudaDevAttrMemSyncDomainCount. Hopper has 4 domains. To facilitate portable code, domains functionality can be used on all devices and CUDA will report a count of 1 prior to Hopper.

Having logical domains eases application composition. The default mapping is to map the default domain to 0 and the remote domain to 1 (on GPUs with more than 1 domain).

A typical use would set the mapping at stream level and the logical domain at launch level.

???

3.2.8 Asynchronous Concurrent Execution

3.2.8.1 Concurrent Execution between Host and Device

The following device operations are asynchronous with respect to the host:

- Kernel launches;

- Memory copies within a single device’s memory;

- Memory copies from host to device of a memory block of 64 KB or less;

- Memory copies performed by functions that are suffixed with Async;

- Memory set function calls.

Programmers can globally disable asynchronicity of kernel launches for all CUDA applications running on a system by setting the CUDA_LAUNCH_BLOCKING environment variable to 1. This feature is provided for debugging purposes only and should not be used as a way to make production software run reliably.

Async memory copies might also be synchronous if they involve host memory that is not page-locked.

3.2.8.2 Concurrent Kernel Execution

3.2.8.3 Overlap of Data Transfer and Kernel Execution

3.2.8.4 Concurrent Data Transfers

3.2.8.5 Streams

Applications manage the concurrent operations described above through streams.

You can also refer to here

3.2.8.5.1 Creation and Destruction

Creation

cudaStream_t stream[2];

for (int i = 0; i < 2; ++i)

cudaStreamCreate(&stream[i]);

float* hostPtr;

cudaMallocHost(&hostPtr, 2 * size);

Definition

for (int i = 0; i < 2; ++i)

{

cudaMemcpyAsync(inputDevPtr + i * size, hostPtr + i * size, size, cudaMemcpyHostToDevice, stream[i]);

MyKernel <<<100, 512, 0, stream[i]>>> (outputDevPtr + i * size, inputDevPtr + i * size, size);

cudaMemcpyAsync(hostPtr + i * size, outputDevPtr + i * size, size, cudaMemcpyDeviceToHost, stream[i]);

}

Release

for (int i = 0; i < 2; ++i)

cudaStreamDestroy(stream[i]);

In case the device is still doing work in the stream when cudaStreamDestroy() is called, the function will return immediately and the resources associated with the stream will be released automatically once the device has completed all work in the stream.

3.2.8.5.2 default stream

#define CUDA_API_PER_THREAD_DEFAULT_STREAM 1cannot be used to enable this behavior when the code is compiled bynvccasnvccimplicitly includes cuda_runtime.h at the top of the translation unit. In this case the--default-stream per-threadcompilation flag needs to be used or theCUDA_API_PER_THREAD_DEFAULT_STREAMmacro needs to be defined with the-DCUDA_API_PER_THREAD_DEFAULT_STREAM=1compiler flag.

The NULL stream is special as it causes implicit synchronization. For code that is compiled without specifying a --default-stream compilation flag, --default-stream legacy is assumed as the default.

3.2.8.5.3 Explicit Synchronization

There are various ways to explicitly synchronize streams with each other.

// waits until all preceding commands in all streams of all host threads have completed.

cudaDeviceSynchronize();

// waits until all preceding commands in the given stream have completed.

cudaStreamSynchronize();

// makes all the commands added to the given stream after the call to cudaStreamWaitEvent()delay their execution until the given event has completed.

cudaStreamWaitEvent();

// a way to know if all preceding commands in a stream have completed.

cudaStreamQuery();

3.2.8.5.4 Implicit Synchronization

Two commands from different streams cannot run concurrently if any one of the following operations is issued in-between them by the host thread:

- a page-locked host memory allocation,

- a device memory allocation,

- a device memory set,

- a memory copy between two addresses to the same device memory,

- any CUDA command to the NULL stream,

- a switch between the L1/shared memory configurations.

applications should follow these guidelines to improve their potential for concurrent kernel execution:

- All independent operations should be issued before dependent operations,

- Synchronization of any kind should be delayed as long as possible.

3.2.8.5.5 Overlapping Behavior

On devices that do not support concurrent data transfers, the two streams of the code sample of Creation and Destruction do not overlap at all.

If the code is rewritten the following way (and assuming the device supports overlap of data transfer and kernel execution)

for (int i = 0; i < 2; ++i)

cudaMemcpyAsync(inputDevPtr + i * size, hostPtr + i * size, size, cudaMemcpyHostToDevice, stream[i]);

for (int i = 0; i < 2; ++i)

MyKernel <<<100, 512, 0, stream[i]>>> (outputDevPtr + i * size, inputDevPtr + i * size, size);

for (int i = 0; i < 2; ++i)

cudaMemcpyAsync(hostPtr + i * size, outputDevPtr + i * size, size, cudaMemcpyDeviceToHost, stream[i]);

then the memory copy from host to device issued to stream[1] overlaps with the kernel launch issued to stream[0].

On devices that do support concurrent data transfers, the two streams of the code sample of Creation and Destruction do overlap.

3.2.8.5.6 Host Functions (Callbacks)

The runtime provides a way to insert a CPU function call at any point into a stream via cudaLaunchHostFunc(). The provided function is executed on the host once all commands issued to the stream before the callback have completed.

The commands that are issued in a stream after a host function do not start executing before the function has completed.

A host function enqueued into a stream must not make CUDA API calls (directly or indirectly), as it might end up waiting on itself if it makes such a call leading to a deadlock.

3.2.8.5.7 Stream Priorities

The relative priorities of streams can be specified at creation using cudaStreamCreateWithPriority(). The range of allowable priorities, ordered as [ highest priority, lowest priority ] can be obtained using the cudaDeviceGetStreamPriorityRange() function.

3.2.8.6 Programmatic Dependent Launch and Synchronization

Available starting with devices of compute capability 9.0, Programmatic Dependent Launch can provide performance benefits when the secondary kernel can complete significant work that does not depend on the results of the primary kernel.

3.2.8.6.2 API Description

In Programmatic Dependent Launch, a primary and a secondary kernel are launched in the same CUDA stream. The primary kernel should execute cudaTriggerProgrammaticLaunchCompletion with all thread blocks when it’s ready for the secondary kernel to launch. If the primary kernel doesn’t execute the trigger, it implicitly occurs after all thread blocks in the primary kernel exit.

when the secondary kernel is configured with Programmatic Dependent Launch, it must always use cudaGridDependencySynchronize to verify that the result data from the primary is available.

This behavior is opportunistic and not guaranteed to lead to concurrent kernel execution. Reliance on concurrent execution in this manner is unsafe and can lead to deadlock.

3.2.8.6.3. Use in CUDA Graphs

skip…

3.2.8.7 CUDA Graphs

Work submission using graphs is separated into three distinct stages: definition, instantiation, and execution.

3.2.8.7.1 Graph Structure

An operation forms a node in a graph. The dependencies between the operations are the edges.

Scheduling is left up to the CUDA system.

3.2.8.7.1.1 Node Type

A graph node can be one of:

- kernel

- CPU function call

- memory copy

- memset

- empty node

- waiting on an event

- recording an event

- signalling an external semaphore

- waiting on an external semaphore

- conditional node

- child graph: To execute a separate nested graph, as shown in the following figure.

3.2.8.7.1.2 Edge Data

Edge data modifies a dependency specified by an edge and consists of three parts: an outgoing port, an incoming port, and a type. An outgoing port specifies when an associated edge is triggered. An incoming port specifies what portion of a node is dependent on an associated edge. A type modifies the relation between the endpoints.

Port values are specific to node type and direction, and edge types may be restricted to specific node types. In all cases, zero-initialized edge data represents default behavior. Outgoing port 0 waits on an entire task, incoming port 0 blocks an entire task, and edge type 0 is associated with a full dependency with memory synchronizing behavior.

Edge data is also available in some stream capture APIs.

3.2.8.7.2 Creating a Graph Using Graph APIs

Graphs can be created via two mechanisms: explicit API and stream capture.

// Create the graph - it starts out empty

cudaGraphCreate(&graph, 0);

// For the purpose of this example, we'll create the nodes separately from the dependencies to

// demonstrate that it can be done in two stages. Note that dependencies can also be specified

// at node creation.

cudaGraphAddKernelNode(&a, graph, NULL, 0, &nodeParams);

cudaGraphAddKernelNode(&b, graph, NULL, 0, &nodeParams);

cudaGraphAddKernelNode(&c, graph, NULL, 0, &nodeParams);

cudaGraphAddKernelNode(&d, graph, NULL, 0, &nodeParams);

// Now set up dependencies on each node

cudaGraphAddDependencies(graph, &a, &b, 1); // A->B

cudaGraphAddDependencies(graph, &a, &c, 1); // A->C

cudaGraphAddDependencies(graph, &b, &d, 1); // B->D

cudaGraphAddDependencies(graph, &c, &d, 1); // C->D

3.2.8.7.3 Creating a Graph Using Stream Capture

A call to cudaStreamBeginCapture() places a stream in capture mode. When a stream is being captured, work launched into the stream is not enqueued for execution. It is instead appended to an internal graph.

Work can be captured to an existing graph using cudaStreamBeginCaptureToGraph(). Instead of capturing to an internal graph, work is captured to a graph provided by the user.

3.2.8.7.3.2.1 Cross-stream Dependencies and Events

// stream1 is the origin stream

cudaStreamBeginCapture(stream1);

kernel_A<<< ..., stream1 >>>(...);

// Fork into stream2

cudaEventRecord(event1, stream1);

cudaStreamWaitEvent(stream2, event1);

kernel_B<<< ..., stream1 >>>(...);

kernel_C<<< ..., stream2 >>>(...);

// Join stream2 back to origin stream (stream1)

cudaEventRecord(event2, stream2);

cudaStreamWaitEvent(stream1, event2);

kernel_D<<< ..., stream1 >>>(...);

// End capture in the origin stream

cudaStreamEndCapture(stream1, &graph);

// stream1 and stream2 no longer in capture mode

When a stream is taken out of capture mode, the next non-captured item in the stream (if any) will still have a dependency on the most recent prior non-captured item, despite intermediate items having been removed. ???

3.2.8.7.3.2 Prohibited and Unhandled Operations

capture ≠ execution

capture = group: query anyone = query group; same with synchronize.

Note that implicit synchronization.

As a general rule, when a dependency relation would connect something that is captured with something that was not captured and instead enqueued for execution, CUDA prefers to return an error rather than ignore the dependency. An exception is made for placing a stream into or out of capture mode; this severs a dependency relation between items added to the stream immediately before and after the mode transition.???

It is invalid to merge two separate capture graphs by waiting on a captured event from a stream which is being captured and is associated with a different capture graph than the event. ???

It is invalid to wait on a non-captured event from a stream which is being captured without specifying the cudaEventWaitExternal flag.

3.2.8.7.3.3. Invalidation

invalid operation -> invalidate stream capture -> invalidate capture graphs. Further use is invalid and will return an error,

3.2.8.7.4 CUDA User Objects

skip…

3.2.8.7.5. Updating Instantiated Graphs

skip…

3.2.8.8 Events

skip…

3.2.8.9 Synchrinoud Calls

skip…

3.2.9 Multi-Device System

skip…

3.2.10 Snified Virtual Address Space

skip…

3.3 Versioning and Compatibility

3.4 Compute Modes

3.5 Mode Switchers

3.6 Tesla Compute Cluster Mode for Windows

4. Hardware Implementation

5. Performance Guidelines

6. CUDA-Enabled GPUs

7. C++ Language Extensions

8. Cooperative Groups

9. CUDA Dynamic Parallelism

10. Virtual Memory Management

11. Stream Ordered Memory Allocator

12. Graph Memory Nodes

13. Mathematical Functions

14. C++ Language Support

15. Texture Fetching

16. Compute Capabilities

17. Driver API

18. CUDA Environment Variables

19. Unified Memory Programming

20. Lazy Loading

Thanks to Lazy Loading, programs are able to only load kernels they are actually going to use, saving time on initialization. This reduces memory overhead, both on GPU memory and host memory.

Lazy Loading is enabled by setting the CUDA_MODULE_LOADING environment variable to LAZY.